TYPES OF OCD

A clarification about the different types of OCD

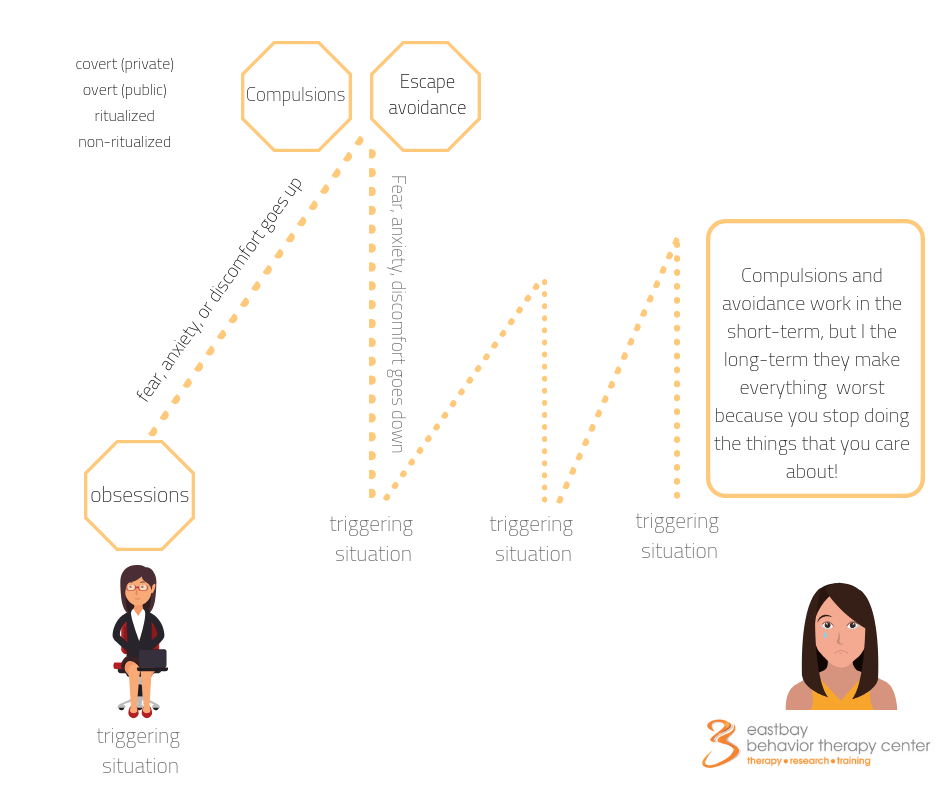

All forms of OCD are maintained by avoidance and compulsions

aggressive ocd

What is it?

The theme of these intrusions is about harming yourself or others as either a direct or indirect result of your actions.

Aggressive obsessions can involve fears of self-harm or of causing harm to others either by lethal forms of harm (e.g., stabbing, suffocating, strangling, shooting, poisoning oneself or another) or because of carelessness (e.g. “if I don’t pay attention, they may fall down on the stairs” or “If I trip when holding a knife, I may stab them”).

People dealing with aggressive or harm obsessions usually hold on to the thoughts of “Because I think so, it makes me so” or “If I don’t do anything, if I don’t prevent it, it’s the same as me causing it.” It’s as if having these violent images or thoughts makes them a violent person, or reveals their true aggressive persona; and, if they don’t pay attention to them, they believe that they may act on them or accidentally harm others.

Avoidant behaviors may include the avoidance of people who could cause harm, of tools that could be used to harm, and of news, books, movies, or any other material related to harm.

Aggressive or harm compulsions may include checking that someone is okay; asking others if they did anything weird; checking your own intentions (“Did I really want to hurt my kid?”); anticipating future scenarios in case of causing potential harm to yourself or others; analysis of past scenarios or reviewing past scenarios to make sure that nothing has happened and, therefore, your innocent.

How it looks?

Let’s take a look at Sebastian’s experiences with this form of obsession:

Sebastian, a college student, went to visit his parents for the summer. He did the usual summertime activities: going camping, cooking meals together, going for runs with his brothers, watching movies, and teasing his sister on and off. Sebastian was very close to his family and always looked forward to spending time with them after a stressful semester at school.

After watching a documentary about typography, he went to sleep around 11 p.m., as he usually does. While sleeping, Sebastian had a nightmare about “slicing his parents” and woke up thinking about it the following day. Sebastian was shocked at having had that image, because deep down he loved his parents and wouldn’t ever do anything to hurt them or his siblings. Sebastian didn’t know what to make of it, but he kept thinking about whether he actually wanted to do this, so he checked his feelings toward his parents and started writing down the good moments he had with them, to prove to himself that he didn’t want to harm them. He started avoiding being in the kitchen with his parents because he was afraid of holding knives around them and preferred to be with both of them, rather than just one of them, in case he ended up attacking one of them.

contamination ocd

What is it?

This is, perhaps, one of the best-known forms of OCD, since it has been disseminated through social media quite often.

People with fears of contamination get hooked into the fear of “being contaminated” due to direct contact with different substances, such as toxic chemicals, dirt, germs, garbage, sticky substances, bodily fluids (saliva, semen, feces, etc.), and objects that are infected by any of the contaminants.

Everyday compulsive behaviors may include excessive handwashing, excessively long showers, wearing gloves, sanitizing different areas, changing clothing that has been exposed to the street environment before letting it come into contact with furniture in the house, asking others if it’s safe to go to a particular place, or asking if a stain or contaminant that a person stepped in is safe.

Avoidant behaviors usually include staying away from contaminated places such as hospitals, public bathrooms, people who have a particular illness, shaking hands with people who could potentially contaminate them, and so on.

In the past, the literature has included emotional contamination within the subtype of contamination obsessions. However, in recent years, the literature has mentioned a new theme of OCD, metaphysical OCD, that includes obsessions about emotional contamination. Metaphysical OCD is described further in this table.

How it looks?

Let’s think about the following contamination obsessions that Patricia has:

On her way to the grocery store, Patricia saw a reddish stain on the ground. She immediately had the thought, “This could be blood. Did I step on it?” She checked the stain from different angles, trying to figure out if it was dry or not, looking at its size and its texture. She called her friends to ask what they would do, or whether she should throw away the shoes she was wearing.

Patricia felt very embarrassed about having to do all these checking behaviors. She worried about people seeing her doing them, and she felt frustrated with herself for not being able to stop them.

existential ocd

What is it?

This theme of obsessions involves philosophical thoughts, existential matters, and reflections about life issues. While they seem like natural reflections that every person has at one time or another, at some point these thoughts arise alongside extreme distress that is hard to let go of.

Most well-known existential obsessions are about death, life after death, feeling love after death, making the best of life, whether emotions are the right ones in a given situation, immortality, life-after-death experiences, and other similar matters.

Compulsive behaviors may include scanning memories about life events in which a person experienced particular feelings, replaying emotional experiences (such as falling in love, being excited about life, etc.;), dissecting past encounters when having a particular feeling to make sure it was the right one, discussing existential topics or life issues as a form of “figuring them out” and hoping to find the “right response,” searching online about existential matters, and reading books about philosophical matters.

How it looks?

Here is how existential obsessions showed up in Theresa’s daily life:

After meeting with a financial advisor, Theresa agreed that it was important for her to get life insurance to protect her family.

When signing the life insurance form, the advisor lightly asked, “Do you think that you’re living your life as you wanted to?” Theresa paused for a moment and thought about the question. It was as if she was wondering about it for the first time, and she became quiet. After signing the documents, she found herself walking toward her car trying to answer that exact question: “Have I been living my life as I wanted to?” Theresa mechanically started driving the car and couldn’t stop thinking about the question. She started replaying different moments in her life such as, times when she felt connected with others, times that were difficult with her family, and times when she had dating issues. Theresa kept wondering whether she was living life at her best, whether she was making the right choices about how to spend her time and her money, and on and on.

Theresa also pondered at length about the impact of her behavior on others: “Am I doing right by others? Am I having an impact on other people? Am I balancing things out in my life?”

At times, she was able to answer those questions with a partially satisfying response, but the thoughts kept showing up nevertheless, again and again, forcing her on a deep downward spiral of thinking about matters that didn’t have a definite answer.

These thoughts were very stressful for Theresa because she could not let them go even as they exhausted her completely.

hyperawareness ocd

What is it?

This form of OCD is also known as somatic OCD or somatosensory OCD.

This group of fears relates to concerns about the quality of specific involuntary bodily reactions or bodily functions, such as breathing, swallowing, amount of saliva, itching, ringing in the ears, blinking, body smell, just to name a few.

Compulsive behaviors typically include contacting doctors, searching online, and checking the quality and intensity of bodily functions (for example, “Am I breathing the same amount of air as this morning?” or “Is this tingling sensation moving from one finger to another?”).

Because the focus of these obsessions is on functions that happen automatically in a person’s body, people with this form of OCD fear not being able to stop being aware of them (eg “what if I cannot stop paying attention to them and it ruins my life?”) or not being able to distract themselves from them because they’re present at all times.

People struggling with hyperawareness obsessions usually engage in massive dosages of body checking and body scanning. Some carry on with regular day-to-day activities like work and school, and so on; on the surface, they appear fine, because they’re not avoiding any situations or activities. Yet, they’re internally preoccupied and hyperfocused on their bodily sensations.

Despite doctors ruling out medical conditions, people with hyperawareness obsessions get hooked on thoughts about something being wrong with their health, feel a strong need to prevent that potential medical condition from occurring, and continue to engage in checking behaviors and mental compulsions.

How it looks?

Consider Rudolph’s day-to-day experiences with hyperawareness OCD:

When Rudolph was getting a routine teeth cleaning, he noticed that the technician spent more time on his bottom right teeth. At the end of the procedure, Rudolph felt a bit of an itch and sharp sensation in that area, so he immediately asked for a mirror; he checked whether there was an irritation and whether the redness was different than the rest of his gums. He asked the technician multiple times about the irritation and was told that the reaction was normal, but as soon as Rudolph left the dental facility, he searched on his phone about those reactions.

Rudolph found multiple websites. While reading all types of information, he continued to inspect his gums in front of a mirror, asked his wife to contact another dentist just in case, and got hooked on the thought, “I’m afraid that if I don’t do anything about it, my gums can have major problems later on, get weak, and I may even lose bone in that area.”

Rudolph struggled with a fear of having an undiagnosed condition that would get worse, even though doctors had denied that possibility. He got hooked on this obsession and couldn’t let it go, to the point that he concentrated all his efforts, energy, and resources trying to “figure out” what could go wrong with his body in the future.

But he did feel temporarily better when reading blogs, asking his wife to book appointments, monitoring the redness and sharp sensation of his gums when eating different types of food, testing if the temperature of food affected that area, trying different toothpastes, and taking pictures on a daily basis. Rudolph was sad that he couldn’t pursue his passion for art since often he spent most of his time making sure he wasn’t sick.

just-right ocd

What is it?

This classification of OCD usually refers to obsessions about a sensation or feeling that is interpreted as weird, uncomfortable, distressing, or off. Because these obsessions are so sticky – meaning they’re extremely difficult to let go of – a person engages in compulsions related to symmetry, ordering, arranging their physical environment, or any other form of compulsive behavior until the “weird” situation “feels right.” Because of these organizing behaviors, this form of OCD is also known as perfectionistic OCD.

Just-right OCD also includes mental compulsions characterized by a person repeating sayings, making lists, counting words, praying, or the like until the person or their situation feels right.

A popular misconception is that people dealing with these types of obsessions or compulsive behaviors are, in general, very organized, neat, and like perfection, but this is an assumption that is usually very far from the truth.

Yes, some people dealing with this form of obsession may prefer and like to keep things organized, but not everyone who has an obsession or any form of OCD will automatically inherit those preferences.

And, just to make it crystal clear, the compulsions (organizing behaviors) are driven by the wish to avoid the discomfort that comes with the uncomfortable feelings that “something is wrong and off” about any environment or situation. These compulsive behaviors are not necessarily meant to prevent something bad from happening—they’re meant to neutralize, get rid of, or minimize the distress they feel.

How it looks?

Let’s see what Allyson’s struggles with just-right OCD looks like for them:

Allyson engages in mental compulsions related to keeping track of her activities, because she is afraid of losing her mind and decompensating. So every day she matches a word or term with a specific activity. For example, “waking up” is matched to her morning routine, “book” is repeated every time she picks up a book. “Breakfast” is matched to the action of preparing her usual r cereal, but if a different milk or t cereal is used, Allyson adds an additional word to her list, such as. “breakfast-vanilla.” If she has breakfast at her parents’ house, she creates the word “breakfast-mom-vanilla.”

The list of “matching words” grows longer and longer as Allyson moves throughout her day. As she tracks every activity, she sometimes repeats the entire word list a different number of times, until they felt right to her.

If someone talked to Allyson when she was in the middle of doing a mental compulsion, she would get very upset, because she had to restart the mental compulsion. However, people only witnessed her getting abruptly get angry; they didn’t have a clue that Allyson was stuck in her head.

At the end of the day, Allyson, continued her mental compulsion and analyzed whether the list of “matching words” was different than the one from the day before and whether there was a particular meaning inherent in that.

Allyson felt exhausted most of the time, because she spent a significant amount of time in her head, and, while she genuinely cared about connecting with others, she didn’t know how to manage. She felt scared about the outcome of not completing her mental compulsion.

meta ocd

What is it?

This is a fairly new topographical description about obsessions about obsessions and related matters; in other words, the theme of Meta OCD is about OCD itself. Meta OCD may involve issues related to (a) making obsessions worse, (b) doubting about the diagnosis, (c) fears about your character or who you are because of obsessions, or (d) concerns about the appropriateness of treatment. As you can see, this is another example of how the brain can latch onto anything and everything as an obsession and as compulsion.

Some examples of obsessions involve questions like: what if I actually don’t get better? Do I have OCD? Am I faking OCD? How do I know I’m in a good place to leave treatment and not go back to where I was before? Am I lying about having OCD?

Some examples of compulsions could be asking for reassurance from others or searching for all types of mental health resources (self-help books, forums, OCD tests, etc).

How it looks?

Let’s think for a moment of Sidney, who has been struggling with obsessions since adolescence because of fears of contamination and harm. After getting diagnosed with OCD and starting exposure exercises, he spent significant time in his therapy sessions asking his clinician about whether he’s doing the exposures correctly, could they make his OCD worse, and if it’s possible he’s faking OCD to get attention. After therapy, he usually spent a couple of hours searching for the highest rated self-help books, mental – health resources, podcasts that focus on personal growth, anxiety, and OCD. On a weekly basis, Sidney also completed an online version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale to check his scores and see whether his OCD symptoms were worsening.

metaphysical ocd

What is it?

This form of OCD has been recently mentioned in the literature, so there is not much written about it, although quite likely, it has affected the lives of many before now.

When dealing with this theme of obsessions, people get triggered with particular feelings, vibes, or energies as if those internal experiences are symbols, cues, or omens that could cause harm to themselves or others. Some past literature has referred to this theme of obsession as emotional contamination OCD.

Strong beliefs in metaphysical or alternative energies are common in some cultures; and just to clarify, I’m not saying that holding these beliefs is inherently problematic. What is problematic is when an over reactive brain gets hooked on obsessions and compulsions triggered by energies, feelings or vibes and this cycle gets socially reinforced because of cultural messages. For instance, in the area where I live, doing “manifestations or creating manifestos” is a very popular practice; when creating a manifesto you are asked to visualize your future in any area of your life and you’re encouraged to ask the universe for that future to become a reality; creating a manifesto assumes that by imagining your future, you will make it happen which reinforces the idea that you have control over your thoughts and that all those feelings, sensations you experience have a particular meaning.

In other words, there is a difference between practicing some activities flexibly (e.g, doing a visualization exercise of your future) versus rigidly attaching meaning to them -(“if say this, it always means this” or “I cannot say this, because it a manifesto and it may happen.) A reactive brain can easily get hooked onto thoughts such as “because I think so, it makes me so”; “I feel it, therefore it’s true”; “thinking about it, makes it happen” or “feeling this, means this…” As with many forms of OCD, a person with a metaphysical obsession can easily end up attributing power and meaning to every single word, sentence, or feeling, thus establishing a problematic cause-and-effect relationship.

How it looks?

Here is how Fernando experiences metaphysical obsessions:

Fernando loves to explore different types of food, learn different languages, and become immersed in different cultures. He always takes the opportunity to travel with his parents, uncles, and cousins, whether locally, within the country, or internationally. Traveling is Fernando’s passion.

During his senior year in high school, his cohort decided to travel to Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay, and Ecuador. Fernando was looking forward to the trip for months, since he hadn’t been to South America before. He wanted to practice Spanish and see indigenous cultures. During his trip, Fernando had strong vibes when visiting some sites and, when talking to some indigenous people, he started compulsively dissecting the meaning of those vibes and energies.

Fernando’s obsession grew quickly. He started hugging people in different ways based on whether he was feeling bad energy or good energy; he was afraid that something bad would happen to him if he was around bad energy. As he continued traveling, he also continued checking his vibes, or intuitions, about colors, shapes, and activities. With every situation, activity, or person he encountered, he immediately scanned his feelings about them.

Fernando felt very stressed about catching and neutralizing the vibe of things, but he got hooked with the thought that “indigenous people have lived for years in this way, so energy experiences must be true.”

Fernando lost his ability to organize his life around what he cared about. He couldn’t show up as the friend he wanted to be. Fernando felt down, depressed, and sad about his world getting narrower and narrower. He didn’t know how to handle all those horrible feelings he had about many things around him.

moral ocd

What is it?

See Scrupulosity OCD.

How it looks?

pedophile ocd

What is it?

Pedophile OCD encompasses thoughts about molesting children, feeling sexually attracted to children, and committing incest. Unfortunately, this may be one of the most misunderstood forms of OCD, even by some clinicians.

There is a variable that makes this complicated, but not unworkable, when dealing with pedophile obsessions: groinal responses. Everyone experiences groinal responses – tingling, itching, scratchy reactions – and everyone experiences arousal reactions that vary in intensity from moment to moment. These responses are dynamic instead of ecstatic experiences. They are triggered when we’re with our romantic partners, or without them, and when hanging out with people of all ages, including children.

The challenge is that these uncontrollable reactions are quickly interpreted by a reactive brain, eager to prove that something is wrong with the person that has them: it is as if they have those groinal reactions, it means the person wants to act on them.

A person dealing with pedophilia obsessions can easily spend significant amounts of time compulsively replaying past scenarios when dealing with triggering situations, checking their bodily reactions for potential signs of sexual attraction, or anticipating and preventing how they would handle future situations if they were to have them.

But the primary difference is that those with this type of OCD do not want to hurt children; their obsession is with their unwanted thoughts about what could happen.

How it looks?

Let’s consider the situations that Suni went through.

After Suni gave a bath to her 2-year-old daughter and touched her vagina while washing her, Suni had an image of her daughter’s naked body and with it the thought “Am I a pedophile? Did I like touching her parts? Why did I have that image? If I touched her private parts and have this image, it’s because I’m a pedophile.” Suni spent hours and hours replaying other times she gave her daughter a bath, changed her diapers, changed her daughter’s clothes, or held her daughter on her lap. She began to panic.

When having these images, Suni started telling herself, “I’m not a pedophile, I’m not a pedophile. I didn’t do anything, didn’t feel anything.” The thought of being a “pedophile” was 100 percent incongruent with who she wants to be, her character, and her personal values.

On top of all those painful moments rushing through her mind, Suni didn’t share any of this with anybody, because she was hooked on the thought that “saying it out loud” would somehow prove the validity and accuracy of the thought.

Suni felt that she was crazy for having these thoughts, that there was something fundamentally wrong with her for having them, and she didn’t know how to get unstuck from her own mind.

perfectionist ocd

What is it?

See “Just right OCD.”

How it looks?

post-partum ocd

What is it?

This class of obsessions includes intrusive thoughts about either intentionally or accidentally harming one’s own baby (e.g. contaminating the baby with toxic products, doing something inappropriate, transferring bad energies, so on).

It’s extremely distressing and panicky for a parent to experience and acknowledge these intrusive thoughts when they are expected to be happy and bubbly about becoming a parent; and, because of this social pressure, there is much secrecy around this type of obsession.

While most of the literature has suggested that only mothers are affected by postpartum obsessions, there is preliminary research that suggests that fathers experience this form of obsessions as well (Abramowitz, 2001). This, of course, makes sense given that the brain could latch into anything as an obsession and as a compulsion; there is no reason why the overreactive brain of a father cannot latch onto fears of harming a baby, doing something inappropriate, and so on. Obsessions at the end, are not a matter of gender but a matter of a brain perceiving danger when bizarre and non-bizarre thoughts, images, and urges pop up

Compulsions may include: repeatedly checking that the baby’s blankets are not close to his face when he is sleeping, so he doesn’t suffocate; checking multiple times that there are no other objects in the crib; holding a mirror to check if the baby is breathing; checking with sitters to see if the baby is okay; asking people to come over, so that the parent isn’t alone with the baby, and so on.

Avoidant behaviors usually include resisting the following: being alone with the baby, changing the baby’s diapers, being around sharp objects, giving the baby a bath, holding the baby, walking while holding the baby, feeding the baby, and the like.

How it looks?

Let’s look at Sheela’s experience with postpartum OCD following the delivery of her first baby.

Sheela brought her newborn baby home and, in her first weeks, she began to experience all the peaks and valleys that come with caring for a newborn: loving the baby every day, feeling exhausted for not sleeping, learning the baby’s needs, bonding with the baby, watching the baby sleeping, and just living motherhood all the way.

One day Sheela’s baby had a high fever, so Sheela spent time next to her, checking her temperature, giving her liquids, and changing one diaper after another. While changing diapers, Sheela had the thought “What if I insert my finger in my kid’s vagina?” and she got really terrified and disturbed about this thought, as if having it meant she wanted to do so.

Sheela couldn’t let go of this thought. She prayed at night hoping it would go away and that it had never happened. She kept it secret and, a week later told her husband he needed to take time off from work because she couldn’t continue taking care of the baby alone.

As time passed by, Sheela couldn’t stop thinking about the bizarre thought about touching her daughter inappropriately, and she replayed mentally over and over how she had changed her diaper. Sheela couldn’t bear this obsession. She felt terribly guilty about having it and she took it as an indication that she may be secretly wanted to harm her baby – which only made things worse for her.

Sheela was physically exhausted from all the chores that come with taking care of a baby and, on top of that, mentally exhausted for all the efforts she was making in her head to deal with this obsession.

pure o, pure ocd, or mental ocd

What is it?

“Pure OCD” is a term that has created controversy among clinicians, researchers, and OCD sufferers. Because of the way it’s written, it conveys the message that a person dealing with pure OCD only has obsessions, with no compulsions.

Here is my take: there is no need to argue about this label but to understand it within its context,

If you look at the literature on OCD, most of it was focused on public compulsions that are visible to the eyes of everyone and while, there were some writings about people that have mental compulsions, no much was written about it. In fact, we don’t know how many people got undiagnosed because of the lack of awareness of mental compulsions and not knowing they were suffering with OCD.

With the premise, let’s briefly clarify that pure OCD or mental OCD is a myth given that all OCD episodes include both obsessions and compulsions. Even if a compulsion is private, not visible to others, it’s still a compulsion.

These obsessions can be prompted by all types of triggers like fears of getting contaminated, existential themes, doing things right, and everything in between. The key characteristic is that once triggered, the compulsions are private, no one sees them, and even the sufferer doesn’t know that they are engaging in a mental compulsion, because all they’re focused on is getting rid of the distress that comes along with these wacky obsessions.

To make it crystal clear, obsessions may show up as thoughts like “did I? could I? would I? do I want to do x, what if I do …?” And then, the response to those thoughts is more thinking, dwelling, repeating sentences, dissecting, figuring out, and so on.

Table 9.1 in Chapter 9 charts the different forms that mental compulsions have, so you will read more about them there. As an example of what you will read in that chart, some mental compulsions look low-key, like saying sentences, repeating words or counting numbers, but they can also be very complex, like replaying past scenarios over and over until they feel right, because your brain is holding on to a memory that feels safe, right, and blocks the disturbing obsessions.

How it looks?

Let’s go over Jack’s struggles to make sense of mental OCD.

Jack was a lawyer in transition between firms, so he had some extra time on his hands to do fun things. He was watching movies, reading books, going for mini road trips here and there, and generally enjoying his month off. On his way back from eating Thai food, he saw a woman on the train reading the book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. He was kind of curious about the title and asked this person a few questions. At the end of their ride, Jack was quite curious, so he ordered the book on his cell phone.

When reading it, Jack found himself pondering about the purpose of life and whether he was living the life he was supposed to live. He found himself sad, confused and scared about not being able to respond to these questions with any certainty. Jack spent hours trying to remember different life memories from his childhood right up to the present, thinking about whether those moments were truly meaningful for him, if he was living at his best. Sometimes, the more he thought about it, the more he found moments of relief, but, at other times he kept going, because he was worried about missing important indicators that could repeat in the future.

When Jack experienced those thoughts – natural reflective thoughts as they may appear – they came with tons of desperation, distress, and fear, because they could not fully figure them out.

Jack didn’t know that all the overthinking, replaying, and overanalyzing they were doing when trying to solve their obsessions were exactly what was making them feel as if they were losing their minds.

relationship ocd

What is it?

R-OCD, covers obsessions relating to relationships. While initially this category only included obsessions affecting romantic relationships, these days the academic literature also reports cases between parents and children, and even relationships with spiritual authorities.

While it’s natural for all of us to deliberate about the “fit” of a romantic relationship – whether our feelings for our partner are real or not – the high degree of panic, fear, and anguish that comes with these reflections is considered a form of OCD. Reflecting on life matters is one thing, but having obsessions about relationships that are hard to let go of, that are more like sticky thoughts, and that, when unresolved, stop a person from moving forward in their day-to-day activities, is quite another, and can be extremely painful.

Current writings recognize relationship OCD as having two variations: relationship-centered and partner-focused (Doron, G. & Derby, D., 2017). In plain language, these variations can be seen in three types of common obsessions and many variations or combinations of them:

(1) Is this the right relationship for me? (e.g., “Am I just settling down?”; “Would this relationship be a long-lasting one?”)

(2) “Do I really love this person?” (romantic partner, parent, child, religious figure).

(3) “Does this person really love me?”

People struggling with this type of obsession can spend years not fully committing to a partner in a relationship, and it may even appear as if they have “commitment phobia,” whereas they may well be struggling with intrusive thoughts about relationships.

Frequent compulsions may include a person testing their feelings when spending time with their partner (e.g., “Am I in love?”; “Do I feel love?”); searching for that “Aha!” moment, or for warm feelings inside; checking their sense of attraction or their romantic memories; or comparing current feelings with feelings they had with previous partners.

Common public compulsions may include asking for reassurance about being loved, asking others if they observed cues that their partner loves them, discussing the quality of the relationships with their partners.

Avoidant behaviors may include steering clear of the following: saying “I love you” to a partner; responding to compliments about the relationship; or having intimate relationships with romantic partners.

The challenge with these obsessions is that they can go unrecognized for years because they can appear as natural reflections that any thoughtful person has. However, in the day-to-day life of a person suffering with OCD, they’re painful, take them into agony, and keeps them in an analysis-paralysis state. Usually, sufferers cannot make sense of what’s happening to them, because they’re fighting thinking with more thinking.

How it looks?

To understand R-OCD thinking better, let’s briefly think of David.

David is the father of three children, has been married for over 18 years. He works full-time and does his best to have a regular rhythm between work and family life.

One day, his teenage daughter, Martha, started arguing with him about wanting to go for a sleepover. The argument ended up with her being upset and running to her bedroom, and David talking to his wife about how difficult it was to raise teens. The next day, David woke up thinking “Do I love Martha? I guess I do, but is it possible that I don’t?” He felt awful that day and called his wife to ask her if he had ever treated their daughter differently than the other kids. Even though she answered that she’d never noticed anything, David couldn’t stop thinking about it.

At the end of day, when driving to pick his children up from school, he started checking how he felt about his daughter when she was talking, laughing, or listening to music. David even asked his daughter to recall the most challenging conversations they had had together, so when she was recalling those events he could try to remember how he felt about her in those moments, to make sure “he loved her.”

David couldn’t understand what was going on. He was upset with himself for thinking in such a bizarre way, and he was petrified at the idea of “not loving his daughter” – as well as at the thought of “talking to others about it.” He would ask himself “What type of monster am I, if I don’t love my daughter?”

religious ocd

What is it?

See Scrupulosity OCD.

How it looks?

responsibility ocd

What is it?

This category of OCD refers to the unsettling fear of being irresponsible and causing harm or potential harm, whether intentionally or by accident. It is very similar to harm OCD.

The academic literature has highlighted that these OCD sufferers present with an extreme sense of hyper-responsibility about their behaviors and the impact of them on others.

Other authors have tagged obsessions about responsibility as a theme, and that’s how the name of responsibility OCD emerged.

Obsessions about being responsible for causing harm to others can vary from causing death, emotional harm, or other types of harm (such as environmental harm or moral harm). See Harm OCD above for a more elaborate explanation of this.

A subtle difference that some authors note is that, at the core, clients with this form of OCD are engaging in compulsions to prevent not only harm but also to prevent feeling guilty, remorseful, or regretful.

How it looks?

To understand this form of obsessive thinking better, let’s consider Frank:

Frank was very thoughtful about protecting the environment, and during college, he participated in different grassroots activities to create awareness about the interaction between the environment and people’s behavior.

After graduating from college, Frank decided to go to law school to pursue environmental law.

During a lunch gathering, he couldn’t help noticing how his classmates didn’t recycle plates or cups, threw everything to the garbage, and didn’t care about how many plastic utensils they used. Frank felt a strong wave of heat going through his body and thought “What if I don’t do anything about it? Then global warming is going to accelerate. The islands of plastics will grow – and I cannot live with it. What if I don’t do anything about it? Does that make me a bad person? I can’t live with it!”

Frank, started to pick up his classmates’ trash discreetly and to separate the recycling items in a corner of the lunchroom. At the end of the gathering, Frank wondered if he was recycling all the items properly – whether he was leaving toxic residues that could harm the earth and cause death to other species. Frank got hooked onto that thought: “Did I do it right, so the planet doesn’t get more damaged?” After replaying in his mind what he recycled and how he did it, he felt still uncomfortable, so he couldn’t stop asking a classmate next to him: “I did separate recyclable items from non-recyclable ones properly, right?”

Frank’s fear about harming the environment was not so weird, but the degree of guilt, distress, and agony that Frank experienced because of the thoughts made it hard for him to keep going with his learning and school activities. It tortured him.

scrupulosity ocd, moral ocd, and religious ocd

What is it?

Scrupulosity OCD refers to obsessions related to the fear of intentionally or accidentally committing immoral acts, being an immoral person, saying or doing things wrong, or engaging in any form of behavior that goes against a person’s morals, standards, or religious beliefs.

The specifics of an obsession that is incongruent with a person’s religious beliefs varies from person to person, given their religious background. For instance, within the Jewish community some examples of obsessions are fears of violating dietary restrictions or disrespecting the Shabath (Sabbath). For a person from a Christian background, some obsessions involve offending God, going to hell, or disrespecting religious authorities (Huppert & Siev, 2010).

Most common efforts to neutralize those obsessions may include compulsions like: excessive praying, asking for reassurance, figuring out or replaying a religious practice, asking God for forgiveness, confessing sin, repeatedly checking to see if a sin was committed, avoiding spiritual contamination, or avoiding spiritual services or figures that may be triggering.

Unfortunately, those who struggle with this form of obsessions, find it difficult to distinguish religious behavior from compulsive responses to an obsessive fear of not living according to their religious beliefs. In fact, they may see a compulsion as a commendable behavior, even though it’s exhausting, stressful, and hard to handle in their lives.

How it looks?

Let’s look at the daily struggles that Tim encountered.

When Tim was walking in the street, he heard a teenager saying, “Oh gosh, fuck this.” Tim got hooked on the obsession of “what if I’m associated with this person? Then that means I’ll be committing a sin” and got fearful about the possibility committing a sin.

On another occasion, Tim was at a service and got distracted listening to two children talking and playing. He started thinking, “If I wasn’t paying attention, does it mean my faith is not strong enough? Does it mean I don’t care about God?” As a compulsion, Tim told himself, “God knows my heart; God sees what I’m made of; God trusts me.”

For Tim, having obsessions about their morality was really sad, because they grew up valuing their morals and religious principles. Having to question their behavior as immoral or sinful made each one of them overly focused on their thinking, as they spent hours and hours searching for the truth; at the end of each one of those moments of search, they felt discouraged about not finding an absolute answer and felt confused about what type of person they really were or what their true morals were.

sexual orientation ocd, homosexual ocd, and gay ocd

What is it?

This is another form of OCD that is usually misconstrued and underdiagnosed. Common obsessions are about sexual orientation, infidelity, sexual deviations, and, at times, sexual thoughts related to religious authority figures or religious figures (Gordon, 2002).

These forms of obsessions have nothing to do with a person’s view of homosexuality but with intrusive thoughts, worries, fears about feeling attracted to or wanting to be with someone of a different sexual orientation than they’re usually attracted to. This applies to people of all genders and sexual orientations. For instance, a homosexual person could have intrusive thoughts about being straight, and so on.

And, just to make it crystal clear, a core difference between sexual orientation obsessions versus being confused about sexual orientation or having sexual fluidity is that obsessions are extremely upsetting, stressful, pop up out of the blue, and are inconsistent with a person’s history of sexual preferences. Sexual obsessions are also different than sexual fantasies or horny thoughts, because these latter ones involve pleasure, fun, and are enjoyable.

People having sexual obsessions may have thoughts along the lines of “I notice I’m paying more attention to girls than guys – like, I like checking them out, and checking how cute they are. Is that because I’m gay?”

Sometimes people stressed with this form of obsessions are terrified that, somehow, they’re in denial of their real sexual orientation, and entertain thoughts such as “Maybe I’m just scared about coming out. Maybe one day I’ll wake up and I’ll have to come out of the closet.”

Compulsive behaviors may include checking whether a sufferer feels more attracted to people of a different sexual orientation than they’re usually attracted to; checking their desire to have sexual contact with the other person, (e.g., “Do I want to kiss her?”; “Do I want to have sex with them?”); testing their intentions when hanging out with others of a different sexual orientation; figuring out the physical sensations they experience; trying to find the meaning of having these thoughts; confessing their thoughts about their opposite sexual orientation as a way to validate and reassure themselves what they’re not.

Avoidant behaviors usually include minimizing contact with people who are triggers and cutting down on watching TV shows or any social media related to people of the sexual orientation that is a trigger for them.

How it looks?

Consider Tom’s experience with these forms of obsessions to make sense of what he went through.

Tom had felt attracted to boys since he was a child. He had a crush on his best friend in elementary school, but didn’t say or do much about it because of his religious background. During his adolescent years, he had sexual encounters with both boys and girls and, as time went on, around the age of 16, he came out as gay. He continued with his life, living as a homosexual and having different partners, went to college, graduated, and started his own company, but in his late thirties, he had a dream about being straight and having sex with a woman. Tom woke up in the middle of the night, hyperventilating and feeling frightened.

Tom started journaling all the reactions he had when interacting with women –watching movies, shows, or commercials involving women, checking if he had any physical attraction to them – and he started to engage in more stereotypical gay behaviors to prove to himself he was gay.

Tom also started replaying all the relationships he had had with women before, trying to remember how it felt to be with them, checking what type of feelings he had for them and whether he got turned on or not. He often got hooked on the thought, “What if I’m straight and I just have been denying it all this time?”

The hardest part for Tom was that he really cared for his relationships, all of them; dealing with these sexual obsessions, led him to isolate, avoid hanging out with the people he cared about, doubt himself, and waste hours and hours stuck in his head.

somatic or somatosensory ocd

What is it?

See Hyper-awareness OCD.

How it looks?

suicidal and self-harm ocd

What is it?

Suicidal or parasuicidal behaviors are usually associated with mood disorders such as depression or bipolar disorder, and chronic emotion regulation problems.

However, because an overactive brain has the natural capacity to latch onto any thought, there are also people who experience intrusive thoughts about committing suicide or doing self-harm behaviors; these thoughts are very upsetting and stressful to them because they’re far removed from their intentions.

The variety of suicidal and self-harm obsessions may vary from feeling terrified about getting depressed and committing suicide, jumping off a bridge, slitting wrists, intentionally losing control and crashing a car when driving, or even a fear of overdosing with medications, just to name a few.

Suicidal obsessions may appear in any form, like images of a person committing suicide, or self-harm behaviors, or thoughts of “What if …?” or “Do I want to …?” Sometimes a person’s brain may link strong sensations in their body with wants or urges to engage in suicidal or para-suicidal behaviors. For instance, if a person is randomly walking in the street and feels a strong rush in their body, their brain may associate that strong rush with obsessions about wanting to die; then, the person may report this association like “It feels as if I want to run to the car and kill myself.”

Talking about death, suicide, or self-harm has been another taboo topic for years. It’s only recently that we’ve had more education and information about it. Yet, there is not much information about intrusive thoughts surrounding this theme, so it can be extremely distressful for the OCD sufferer, and also for a therapist who is not familiar with OCD. If a person reports suicidal thoughts, a clinician may conduct a risk assessment and even request hospitalization; this is necessary in some cases but can actually be counterproductive in others. When a person is dealing with obsessions focused on suicide, a risk assessment or exploring their feelings around it can inadvertently reinforce the OCD cycle because it leads to more compulsions and reassurance-seeking behaviors.

And just to clarify, this doesn’t mean that a person suffering with OCD cannot attempt suicide – they certainly can. The point is that when having a suicidal thought, we cannot automatically assume that a person wants to die.

How it looks?

For a moment, let’s consider Thomas’ experience with these obsessions and how they unfolded into his day-to-day life:

Thomas, an engineer in his mid-30s, was driving back from a long meeting at work and found himself appreciating the structure of the bridge he was driving on. While thinking of the amount of heavy work and calculations required to build it, he suddently had the thought “What if I jump off the bridge?” Thomas was perplexed at thinking that way, and then his mind continued: “Do I want to jump off the bridge? Does it mean I want to do this?”

Thomas started telling himself compulsively “I am not going to do that; I don’t want to do that, but I can do so. Is there any part of me that wants to do so?” He then spent the rest of his commute listing all the events that happened recently that would indicate there was a part of him that wanted to die: a project didn’t go well at work, his boss got fired, he didn’t like his new boss, his wife was unhappy with the number of hours he worked, his friends complained that he didn’t have much time for them, his parents had passed away the previous year, and his kids barely wanted to spent time with him now that they were teenagers.

After all that thinking, Thomas felt much more distressed at the idea that he may unconsciously have wanted to die – that he could commit suicide and may have wanted to do so; he also got petrified at the possibility of not being aware of his wants, which meant that “he may be decompensating and [was] not fully aware of the seriousness of what’s he [was] going through.”.

Thomas started researching symptoms of depression and signs of a suicide wish, and he contacted the suicide crisis line a couple of times. He had no idea he was dealing with OCD. His over-reactive brain jumped onto every clue that indicated he had the potential to harm himself. It was a nightmare for him to leave his house, go to work, and take his brain with him.

JOIN

THE EARLY WAITLIST

Enter your e-mail & be the first to know when ACT BEYOND OCD, adult & teen track, opens for registration!

(Only twice a year)

What if most of the chaos in your mind goes to the background by learning research-based life skills and getting clear about what matters to you?

Subscribe to my monthly newsletter playing-it-safe.

Get real, practical, and research-based skills to stop "playing-it-safe" and get unstuck from worries, fears, anxieties, obsessions, and panic.

Frequently asked questions about ACT beyond OCD

What is OCD?

Are there different types of OCD?

How do I know I'm doing mental compulsions?

Why is it so hard to let go of obsessions?

Are there memoirs about OCD that I can read?